10 Years of Wasm: A Retrospective

In April of 2015, Luke Wagner made the first commits to a new repository called WebAssembly/design, adding a high-level design document for a “binary format to serve as a web compilation target.”

Four years later, in December 2019, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) officially embraced WebAssembly (Wasm) as the “fourth language of the web”. Today, Wasm is used in web applications like Google Earth and Adobe Photoshop, streaming video services like Amazon Prime Video and Disney Plus, and game engines like Unity. Wasm runs on countless embedded devices, and cloud computing providers use Wasm to provide Functions-as-a-Service (FaaS) and serverless functionality.

The road to standardization (and understated ubiquity) would require the teams behind the major browsers to unite behind an approach to solve a problem that many had tried, and failed, to solve before.

For the ten-year anniversary of the project (well, ten and change), I spoke to many of the co-designers who were there at the beginning. They were generous enough to share their memories of the project’s origins, and what they imagine for the next ten years of WebAssembly.

The trusted call stack

In March of 2013, a group of Mozilla engineers including Wagner, Alon Zakai, and Dave Herman released asm.js. asm.js defined a subset of the existing JavaScript language that implicitly embeds enough static type information to allow a browser’s existing JS engine to achieve much better performance once the optimizer knew to look for it. “Super hacky,” in Wagner’s words.

Meanwhile, Google was developing Native Client (NaCl) and its successor Portable Native Client (PNaCl), to sandbox and run native code in Chrome.

JF Bastien was on the Chrome team at the time, where he helped finalize the Armv7 version of NaCl. According to Bastien, NaCl was a secure sandbox, but it wasn’t portable, and didn’t “fully respect the ethos of the web.”

PNaCl placed untrusted code in a separate process from the rest of a web page and its JavaScript—a reasonable choice for sandboxing, but one that made it difficult for JavaScript to call PNaCl code or vice versa. The connection between PNaCl and the rest of the browser relied on message passing, which required an entirely separate API surface for graphics, audio, and networking. It also forced asynchrony as a programming model, a huge lift to execute successfully. This created obstacles to broader adoption. If PNaCl was going to serve as the basis for a multi-browser approach to native code on the web, what standards body would govern the APIs?

asm.js took a different approach, which Dan Gohman—then at Mozilla—describes as a “trusted call stack,” where compiled code and JavaScript could share the same stack.

“That means asm.js was able to coexist with JavaScript,” he says. “You can call into JavaScript, and JavaScript can call into you.” This design decision—later inherited by WebAssembly—would prove foundational, enabling everything from seamless browser integration to calling functions across isolation boundaries in the Component Model.

“We’re going to tell each other’s managers that the other one’s on board.”

By the end of 2013, developers were already compiling C++ games to asm.js using the Emscripten toolchain, created by Alon Zakai. The Mozilla team was contemplating whether and how to integrate asm.js into the browser as a solution for running native code.

At Google, the V8 team used asm.js workloads as one of the benchmarks for a new optimizing compiler called TurboFan. Ben Titzer led the TurboFan effort. Like many of the Wasm co-designers, he was social with engineers at Mozilla, Apple, and Microsoft. Sometimes people moved from one company’s browser team to another, and working in the space led naturally to collaboration and more casual socialization. “Drinking and talking about the web,” as Bastien says.

One day, Titzer got into conversation with Wagner about the Mozilla team’s plans for asm.js.

“We’re talking to the Google folks,” Wagner says, “and they were like, ‘We hate this. It’s weird, it’s gross, it’s ad hoc—why would you even do this? If you want to do this, just do a real bytecode.’ And we said: well, we could, and this would be the polyfill of it.”

“[asm.js] fundamentally depended on things like array buffers being efficient,” Titzer recalls. “I remember having a conversation with Luke about resizable array buffers and whether they could be detached. He was basically trying to convince us that this is a good thing. And he had mentioned off-handedly that maybe Mozilla were thinking that asm.js wasn’t the right way to go. Maybe we should design a bytecode. And my ears perked up at that.”

Titzer and Wagner agreed to work together on the project, but now they needed to secure broader buy-in. Together, Wagner says, he and Titzer made a plan: “We’re going to tell each other’s managers that the other one’s on board.”

Titzer began building prototypes, and by late 2014, the V8 team’s interest gave the effort critical momentum. Soon the PNaCl team at Google signed on, and Bastien became one of the project’s key organizers.

Neither web, nor assembly?

When someone defines WebAssembly, odds are even that they’ll adapt the old joke about the Holy Roman Empire to say the technology is “neither web, nor assembly.” That is to say, it’s neither specific to the web nor strictly an assembly language, but rather a bytecode format targeting a virtual instruction set architecture.

So where, exactly, did the name come from?

“We wanted asm in it because of the asm.js heritage,” Wagner says, “and we wanted web because all the cool standards of the time had web, like WebGL, WebGPU…we wanted to be very clear that this is a a pro-web thing.”

The co-designers briefly considered “WebAsm” but (perhaps wisely) passed on that one. So “Asm” was spelled out into “Assembly.” WebAssembly.

Bastien recalls internal resistance to the name. “We know it’s going to be used outside the web,” he says. “We’re designing it to be used outside the web.” But no other suggestions were forthcoming, and “WebAssembly” stuck.

This writer has certainly used the “neither web nor assembly” line more than once, and so did several of the Wasm co-designers I interviewed, but Wagner gently pushes back on the characterization.

“Setting aside the asm.js path dependency, perhaps ‘bytecode’ or ‘intermediate language’ would’ve been a bit more accurate,” he says, “but when people say it’s not ‘web’ because it’s being used outside the web… well, what’s the definition of the web? Is it only things in browsers? The W3C paints a much broader picture of the open web platform that I think covers a lot more of the places where WebAssembly runs today and where we want it to run in the future.”

“Ship as fast as you humanly can before this whole coalition falls apart.”

With the Chrome and Firefox teams on the same page, the co-designers turned to the teams at Apple and Microsoft.

Microsoft’s Chakra team, which powered the Edge browser’s JavaScript engine, had already implemented asm.js optimizations—Wagner had personally relicensed Mozilla source code to make adoption easier. After some “intense Q&A” (in Wagner’s words), the Chakra team got on board. At Apple, JavaScriptCore team lead Fil Pizlo (the same Fil of Fil-C) was instrumental in securing buy-in.

The four browser engines—Mozilla’s SpiderMonkey, Google’s V8, Microsoft’s Chakra, and Apple’s JavaScriptCore—would ship WebAssembly support within months of each other. Bastien, who chaired the WebAssembly Community Group during this period, helped set up the organizational structure and operating pace for the W3C standardization process. Before Wagner’s first public commit, the team hashed out the basic shape of the project in a shared Google Doc. Wagner then transcribed those agreements into public markdown files.

The formal announcement was coordinated: on June 17, 2015, all four browsers simultaneously released blogs linking to each other. Brendan Eich posted his own blog, giving the project the imprimatur of JavaScript’s creator, and riffing on his trademark close to presentations:

I usually finish with a joke: “Always bet on JS”. I look forward to working “and wasm” into that line — no joke.

As the project progressed, Lin Clark’s communication was instrumental in building community understanding, such as in Mozilla blogs like Creating and working with WebAssembly modules.

For the group working on Wasm, the pressure to ship was intense. “Ship as fast as you humanly can before this whole coalition falls apart,” was the prevailing sentiment, according to Wagner. In retrospect, the urgency proved prescient. Had WebAssembly been delayed, the Spectre vulnerability—disclosed in early 2018—might have complicated the threading story and handed ammunition to those who preferred PNaCl’s out-of-process isolation model. Firefox shipped first in March 2017, with Chrome following weeks later. By the end of the year, all four major browsers supported WebAssembly.

Treating it as a real thing

Wagner remembers discovering that Facebook had quietly integrated asm.js into their site to compress JPEGs before upload. “They didn’t tell us,” he says. “They just did it.”

As Wasm passed from idea to spec to reality, more and more organizations were getting interested. At the second in-person meeting between browser vendors, before the spec was anywhere near complete, a representative from Zynga showed up. Best known at the time for Farmville and other Facebook games, Zynga had built a billion-dollar business on Flash. With Flash on the way to deprecation, they were looking for an alternative.

Gaming had been part of the conversation from the beginning—early demos featured Unity’s “Angry Bots” running across multiple browsers. Now the growing interest of other web application teams was informing the development of the project. Adobe engineer Sean Parent provided crucial early feedback on the need for features like threads and robust compute capabilities, driven by the effort to bring Photoshop to the web.

“I realized that not only was it Zynga, not only was it Unity, but also Adobe wants to ship Photoshop and Google Earth wants to ship a new version of Google Earth,” Titzer says. “I realized that there’s all these huge applications that want to come onto the platform, and they’re treating it as a real thing. That, I think, is the point where I realized this is actually going to be something that makes a huge difference.”

“Name an API in the world and it’s in scope.”

asm.js helped answer the hardest questions for the WebAssembly MVP: What is the security model? What features are in scope? When someone proposed adding coroutines or stack switching, the response was simple, according to Gohman: “That’s not in asm.js. Out of scope. End of story.” While the team allowed “a few things that weren’t first-class in asm.js,” in Bastien’s words, asm.js served as a guiding light.

The next phase of WebAssembly’s evolution offered no such scaffold. With the core spec shipped and browsers onboard, attention turned to running WebAssembly outside the browser—on servers, at the edge, in embedded systems. This meant defining WASI, the WebAssembly System Interface, and eventually the Component Model. Together, these specifications could allow Wasm binaries to communicate with one another. These “Wasm components” would be able to securely interoperate regardless of the language they were written in.

The design space was suddenly vast.

“What surprised me most is how hard it was to figure out what to do for Wasm outside the browser, if not copy POSIX,” Wagner says. The Unix-style approach was tempting—just give WebAssembly modules access to files, sockets, and processes in the familiar way. But Wagner saw a trap. “If you just copy POSIX, you’re just going to have to reimplement containers but with Wasm on the inside,” which is not an unambiguous win: it somewhat improves portability, but imposes execution overhead. And if it’s not a significant improvement, why do a bunch of work on it?

Gohman, who went on to lead much of the WASI design work, recalls the early days as intimidating. “You add WASI to the mix and it’s like, now we’re going to add APIs to everything,” he says. “Graphics, networking, input devices—everything you can do from a browser, but also now we’re in servers too. We’re going to talk about databases. Name an API in the world and it’s in scope for WASI.”

The challenge was compounded by the need to design cross-language APIs without the scaffold of existing standards. Should WASI present a C-style interface? A JavaScript-style one? An RPC protocol? The answer, eventually, was none of the above: the team developed WebAssembly Interface Type (WIT), an interface definition language that can generate idiomatic bindings for any target language.

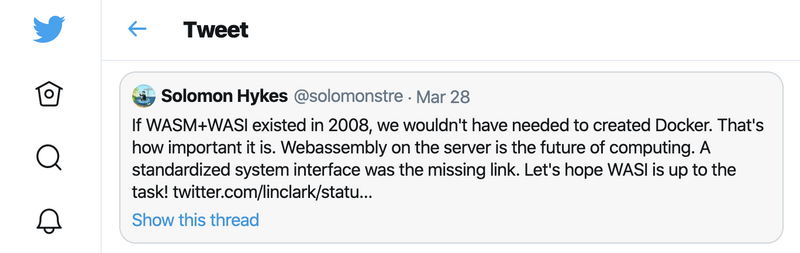

In March 2019, Mozilla announced WASI and caught the attention of Solomon Hykes, creator of Docker. Hykes famously posted on Twitter:

The first iteration, now called WASI Preview 1, provided basic capabilities like file I/O and environment variables, but lacked networking and threading. Lin Clark continued to help communicate the vision for the project in blogs like Standardizing WASI: A system interface to run WebAssembly outside the web.

Five years later, in January 2024, the WASI Subgroup launched WASI 0.2—also known as Preview 2—which incorporated the Component Model and expanded the available APIs.

WASI 0.3 is on the horizon in 2026, bringing native async and cooperative threads, with a 1.0 release set to follow.

The next ten years

Titzer is now Associate Research Professor in the Software and Societal Systems Department at Carnegie Mellon, where he has turned his attention to embedded systems and artificial intelligence—two domains where WebAssembly’s core properties might prove transformative. He’s been working on projects integrating WebAssembly into industrial controllers and cyber-physical systems.

“[Industrial automation companies] have the mobile code problem,” he explains, referring to software that may be transmitted across a network and then executed on a remote machine. “At its core, if Wasm solved any problem, it’s running untrusted mobile code.” The same principle applies to sandboxing AI-generated applications. “You’ve got AI generating code—who knows what it does? Do you trust this code? No.”

Bastien agrees. “AI coding agents are are pretty insecure right now, especially third-party plugins. Forget just injection, right? Like, I’m going to run a bunch of code I don’t trust. Wasm is a pretty interesting fit.”

Meanwhile, some of Wasm’s innovations gleaned outside the browser context may return home. Wagner sees the Component Model improving the quality of web developers’ experience compiling their language of choice to run in the browser, either mixed into their existing mostly-JS web app, or implementing the whole web app itself.

Today, WebAssembly runs in billions of users’ browsers, as well as edge networks, clouds, and embedded systems. The project has achieved standardization and understated ubiquity. It’s almost certainly running in one of your most commonly used apps, on one of your everyday devices, right now. What and where could Wasm be in ten years? The fundamentals of the architecture, going all the way back to asm.js, stuck a toe in the door of a vast possibility space.

In Gohman’s view, WebAssembly represents “one of the few chances that the computing industry has at actually building an execution environment that’s truly cloud native. Wasm combines an architecture which differs from what traditional operating systems are designed around, starting with the trusted call stack, and broad relevance, starting with the Web.” It will take persistence, but for perhaps the first time in fifty years, he says, there’s a chance to innovate at the boundary between kernel and user space.

“It’s gonna be a long road,” he says. “We’re going to build a lot of cool stuff. We’re going to have a lot of fun.”