Bytecode Alliance: One year update

We announced the Bytecode Alliance nearly a year ago, and since then it has been… quite a year 😬

While the 2020-ness of this year has slowed us down on some fronts, we’ve also made a lot of progress on others.

Now that we’ve adjusted to the new normal, we’re gearing up to accelerate on all fronts. But before we do that, we wanted to share some highlights of what we’ve achieved to date.

Progress on the nanoprocess model

Our goal is to evolve WebAssembly from a compilation target that you compile monolithic applications to, to a modular ecosystem that you compose applications from.

As we do this, we have a chance to fix many longstanding problems with the way software is developed. For example, we can make it much safer for your application to use dependencies that you didn’t code yourself.

This is why the nanoprocess model is so important. It’s the paradigm shift necessary to empower developers to defend themselves against these problems.

There are three core pieces of the nanoprocess model that are still in progress:

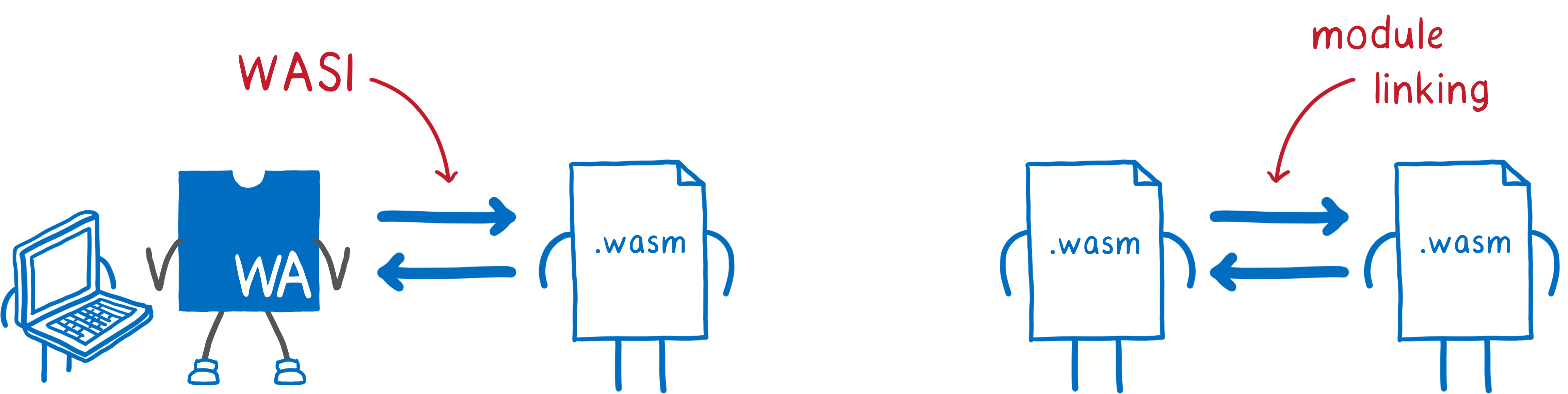

- WASI, the WebAssembly System Interface

- Module linking

- Interface types

You can think of WASI as the way that the host and a WebAssembly module talk to each other.

You can think of module linking as the way that two WebAssembly modules talk to each other.

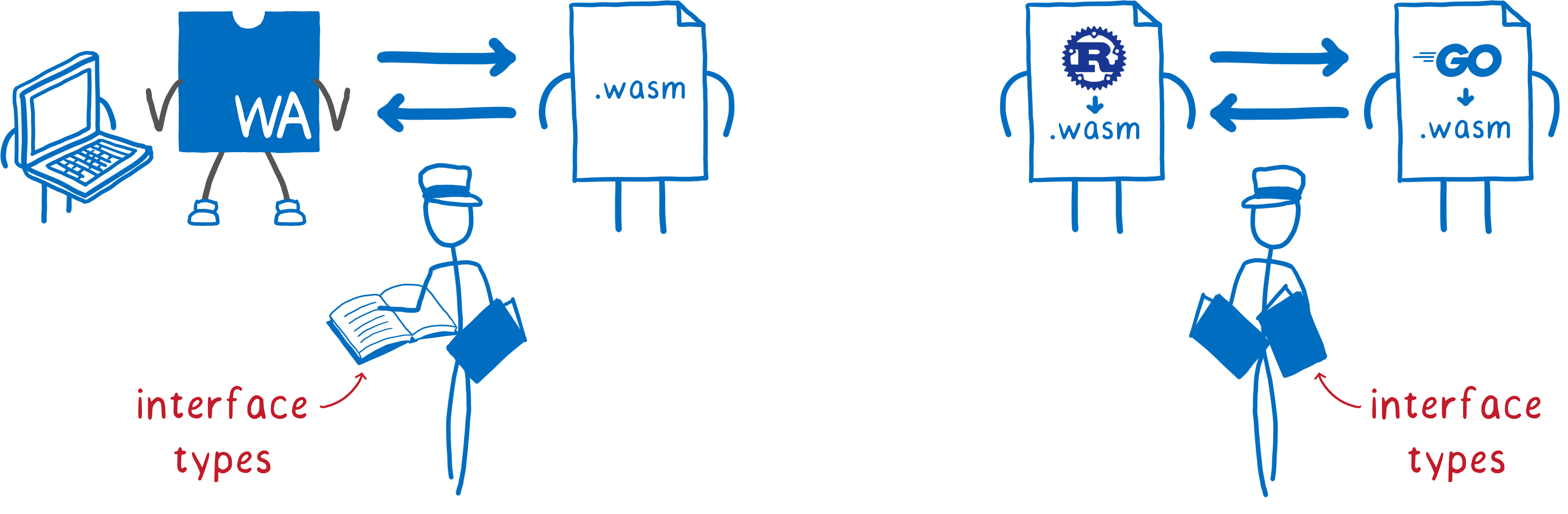

In both of these cases, the two sides are often written in different source languages. This means they might represent values and handles to resources in different ways. Basically, they speak foreign languages.

Interface types are like a foreign-language dictionary that the engine uses to help them communicate.

Let’s see where the work on these stands today.

Note: The Bytecode Alliance doesn’t host specifications. While BA members are driving specs mentioned below, they are doing that in collaboration with others in the W3C WebAssembly CG. Bytecode Alliance projects include implementations of these specs.

WASI, the WebAssembly System Interface

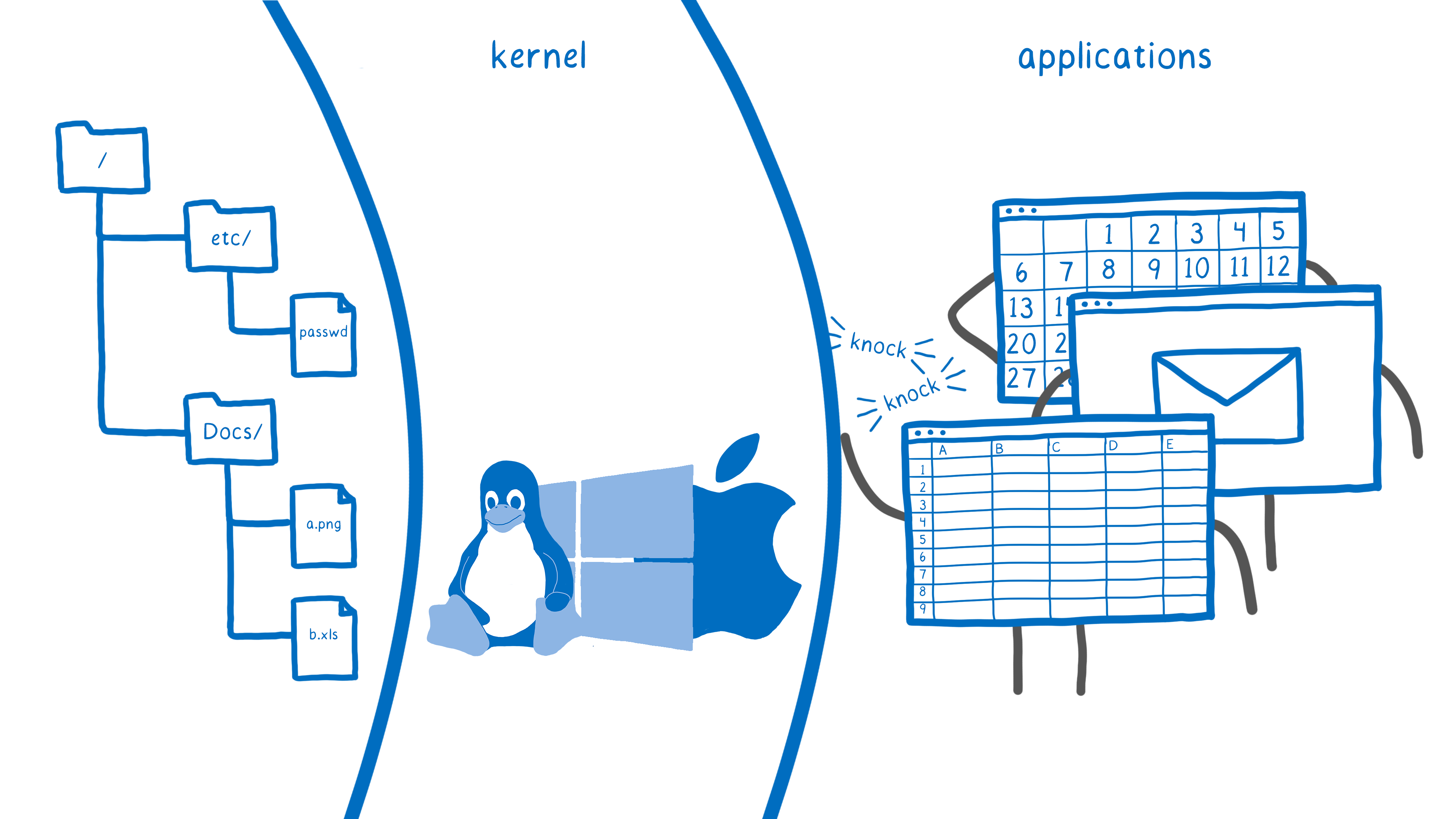

When we introduced WASI, we compared it to POSIX and other system interfaces. That was a bit of an oversimplification, though.

While WASI does aim to provide a set of standardized modules that provide these low-level system interface operations, we also intend to standardize modules for specialized higher-level host APIs.

We’ve made progress on both of these fronts.

Low-level system interface level

For the low-level system interface level, the work has been focused on quality of implementation.

On the spec side, that has been identifying and addressing problems with cross-platform implementability of the spec. One example of this is the wasi-socket API (which was recently prototyped in Wasmtime). In this case, the conversation has centered on the right way to apply capabilities-based security to the handling of sockets.

On the implementation side, we’ve done a lot of work to improve the security and reliability of our implementation. Part of this has been developing robust fuzzing measures (which we describe more below).

Another thing we’ve done is factored out the security-critical operations into a dedicated library, cap-std. It’s a cross-platform library which provides much of the functionality of Rust’s standard library in a capabilities-oriented way. This allows us to fully focus on getting those security-critical foundations right on all platforms. As a next step, we’ll make use of cap-std in our WASI implementation.

Specialized higher-level host APIs

For the specialized higher-level host APIs, there has been exciting work on proposals for completely new API modules.

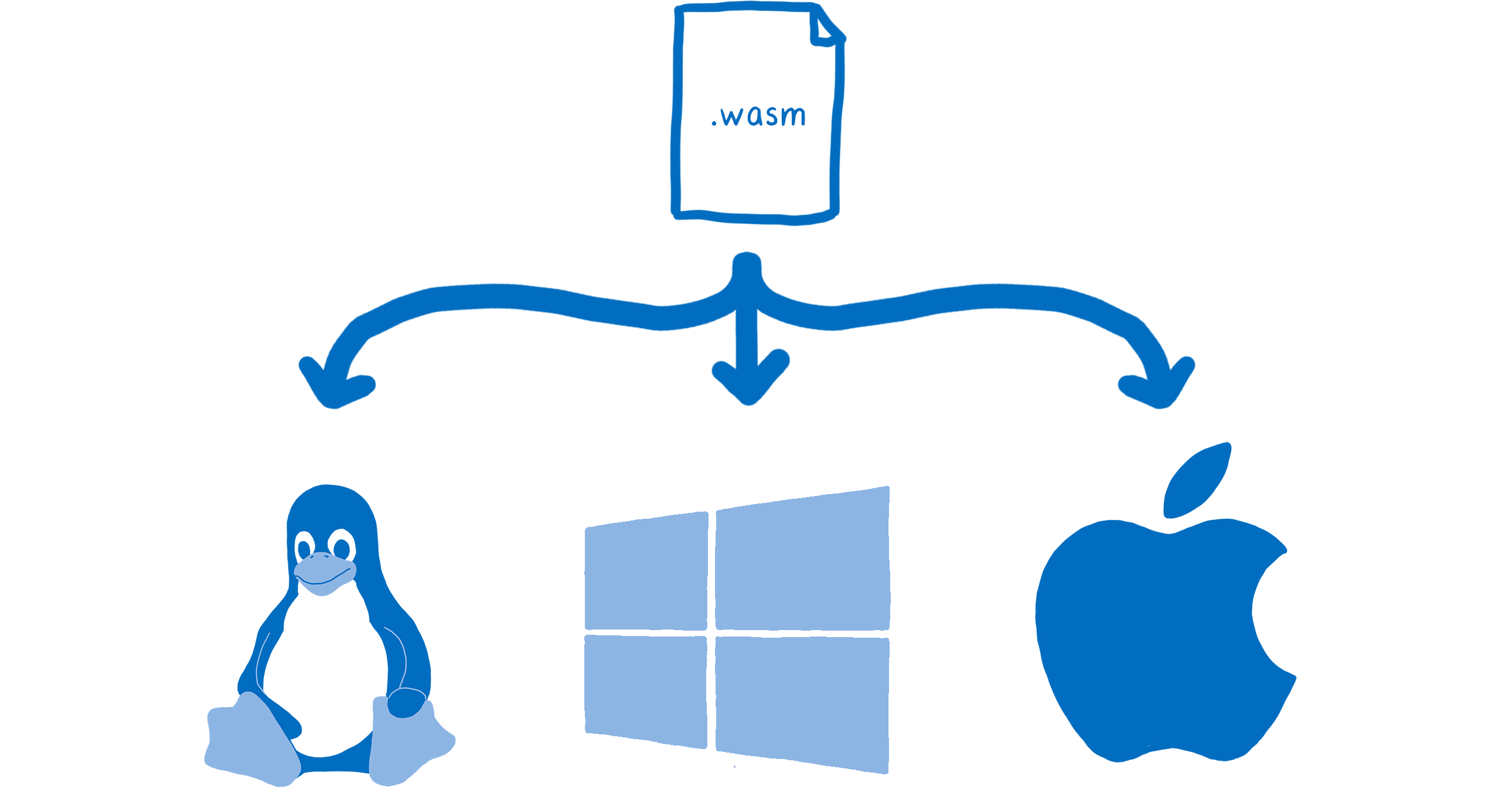

One great example of this is wasi-nn, which is a standardized interface for neural networking. This is useful because trained machine learning models are typically deployed on a variety of different devices with different architectures and operating systems. Using wasi-nn, the .wasm file can do things like describe tensors and execute inference requests in a portable way, regardless of the underlying ISA and OS.

We’re implementing all of these in Wasmtime as they develop. That way, people can try them out and real world usage can inform the specification.

Module linking

If we’re going to have an ecosystem of reusable code, we need a good way to link modules together.

Right now, you can link modules together using host APIs. For example, on the web you can string together a bunch of WebAssembly.instantiate calls to link a set of modules together. In Wasmtime, you use the linker APIs.

But there are a few downsides to this imperative style, including the fact that it’s fairly cumbersome, not that fast and requires the host to include some type of garbage or cycle collector.

With the module linking proposal, linking becomes declarative. This means that it’s much easier to use. It also means that even at compile time, the engine has all of the information about how modules are connected to each other. This opens up lots of potential optimizations and features and removes the possibility of cycles.

For now, we’re focusing on load-time linking, which will enable modules to factor out common library code. And for that, the proposal is pretty much complete. Longer term, we’ll be able to add run-time dynamic linking as well.

Our next step is to finish a prototype implementation, which should be complete within the next few months.

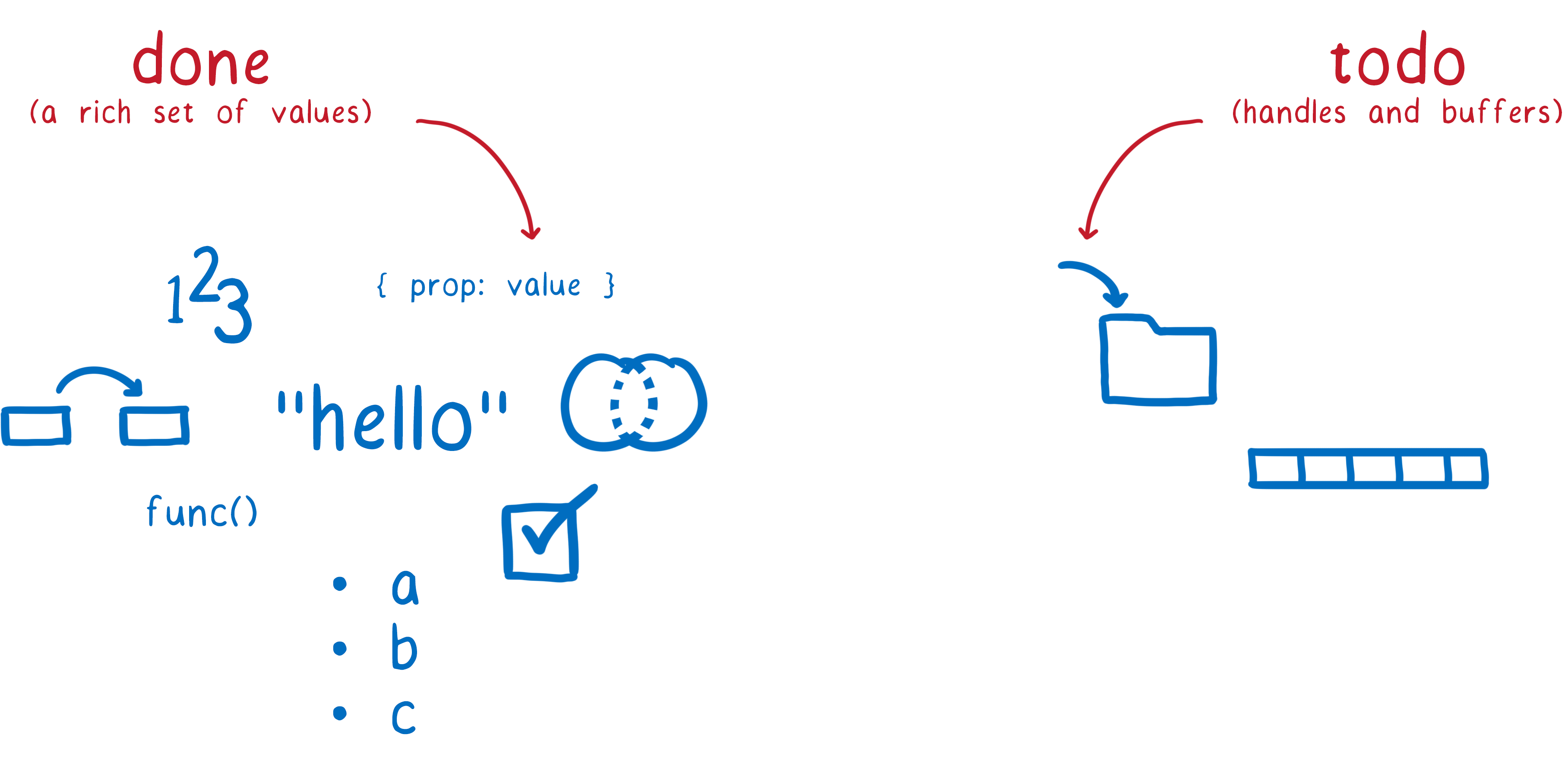

Interface types

The Interface Types proposal is evolving nicely.

Interface Types can now talk about a rich set of values. The design is also more efficient now, removing the need for an intermediate copy of values in almost all cases.

So what’s left to do in the short term?

While Interface Types can talk about values, they can’t yet talk about handles to resources and buffers. Both are important to support WASI and other APIs, because things like files should use handles, and it should be possible to read a file and write directly into a buffer.

Once those features are in place, Interface Types will have everything it needs to support both WASI and Module Linking, making it possible for them to talk about values and resources in a source-language independent way. So we’ll continue working on the spec in the W3C.

On the implementation, we’ve set the stage to execute quickly. We’ve already implemented the new features in Wasm core which Interface Types depend on, such as Reference Types, multi-value, and multi-memory support.

We’re also working on tools for using Interface Types. Currently, people can use wasm-bindgen to create bindings for JS code. In the coming year, we’ll add direct support for Interface Types to language toolchains, starting with Rust.

We expect to complete most of this work within the next six months.

In the meantime, for people wanting to get things done today but in a forward compatible way, you can define your interface using WITX. You can learn more about how to do this from this presentation by Pat Hickey, or this blog post from Radu Matei.

Supporting more languages

To bring the nanoprocess model to as many people as possible, we need to integrate with as many languages as possible.

More languages compiling into the WebAssembly nanoprocess model

If you want to produce code that uses the nanoprocess model, you need a compiler that:

- can target WebAssembly, and

- has support for these cutting edge standards

To help language communities speed up their adoption, we’ve started building out wasm-tools. This is a standard set of tools that other compilers can use to target WebAssembly.

These are all tools that we use in Wasmtime, so as new WebAssembly features come online, they are supported here. For example, we’ve already started building support for module-linking into these tools.

The tools currently include:

wasmparser, which is a parser for WebAssembly files. It’s quite cheap because it doesn’t do any extra allocations, and can parse in a streaming fashion.wasmprinter, which translates a .wasm binary format into the .wat text format, which is useful for debugging and testing.watandwast, which translate the .wat and .wast text formats into the binary format, which is useful for running tests (since it’s easier to maintain tests in the text format).wasm-smith, which is a test case generator. It generates pseudo-random Wasm modules, guaranteed to be valid Wasm modules, which we use for fuzzing.

We will be adding more tools over the next year. For example, we will host the language-independent parts of the Rust Interface Types toolkit in wasm-tools, which will make it easier for languages that compile to WebAssembly to start supporting Interface Types. We also plan to collaborate with language communities on integrating these tools as they come online.

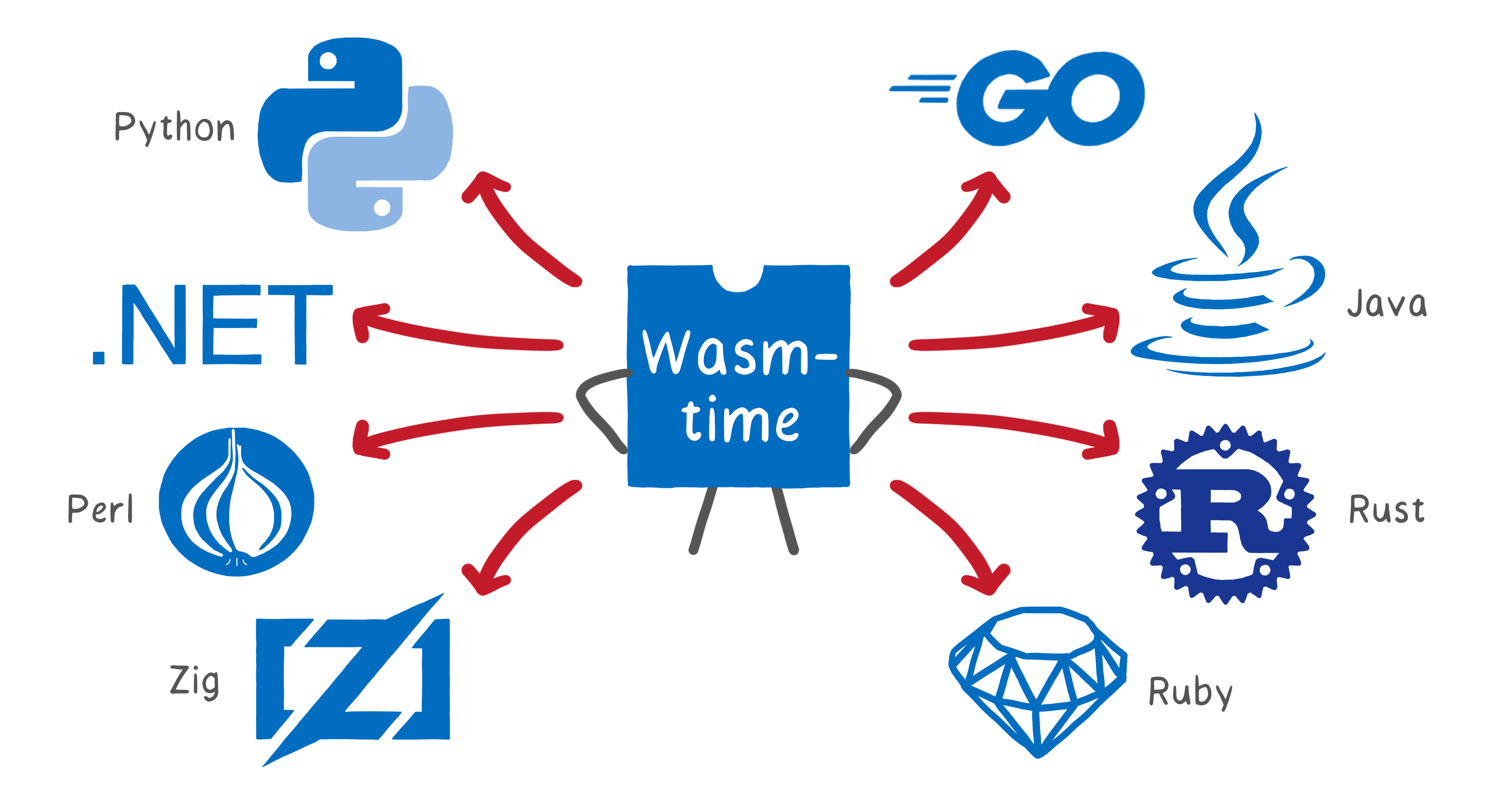

More languages embedding WebAssembly via Wasmtime

If you have a whole WebAssembly application, you can run that directly in a runtime like Wasmtime. But sometimes, you just want to run a little bit of WebAssembly in your project.

For example, you might be writing some Python code, but want to do some intensive computations. Python may be too slow, and native extensions may be too frustrating to use portably, so you could use a WebAssembly module instead.

Wasmtime is enabling this for many languages, through embeddings into the language runtimes.

These languages now have support for running WebAssembly in Wasmtime:

- Python

- Go

- .NET

- Java (two options: kawamuray/wasmtime-java or bluejekyll/wasmtime-java)

- Perl

- Rust

- Zig

- Ruby

As new nanoprocess features come online, they get added to Wasmtime. We don’t consider feature development complete until the feature is exposed in the language embeddings that we maintain. That means that these languages can run the most cutting-edge WebAssembly modules as soon as possible.

It also means that these language communities don’t have to come up with their own ways of doing linking and binding. They can just depend on the WebAssembly standards, which makes everything more interoperable.

In the last year, we’ve transitioned the embeddings we maintain to use the standard Wasm C API, and we’re keeping our Rust embedding API and the C API updated in lock-step.

Wins in multi-stakeholder collaboration

We’ve said it before, but building out these foundations is too big a task to tackle alone. That’s why effective multi-stakeholder collaboration is so important.

Here are some of the changes we’ve made over the past year to make that collaboration even better.

A new backend for Cranelift

Cranelift is the code generator used in many runtimes, including Wasmtime, Lucet, and SpiderMonkey, and other projects like an alternative backend for the Rust compiler. It turns Wasm into machine code. With the new backend, we’ve made it much easier to add support for new ISAs, and to collaborate on improving existing ones.

Cranelift’s previous backend used one intermediate representation (IR) for everything. It also had some obscure abstractions that were hard to work with.

The new system splits the process into two phases, adding a second IR that is machine specific. This way, each IR can be specialized to its task at-hand. The new system also removes the obscure abstractions (you can learn more about this in the Kill Recipes With Fire 🔥 bug).

We also added a new tool called Peepmatic. With this tool, we can apply peephole optimizations when the code is still portable, before we get to the second IR. And we’re in the process of making Peepmatic even more flexible so that we can apply peephole optimizations in the second phase, too, when the IR is machine specific.

The goal is that anything that is not a control-flow transformation can go through Peepmatic. With this, we’ll have a lot less one-off, hand-written code in Cranelift, which improves maintainability.

It also helps with correctness: the DSL Peepmatic uses makes some correctness issues impossible, and is easier to reason about than hand-written code. We also have plans to add verification of our peephole optimizations. This way, we can detect when an optimization isn’t correct for all inputs.

To realize the full potential of Peepmatic and the WebAssembly sandbox in general, we’re working with academic researchers. For example, we’re working with John Regehr and his student Jubi Teneja on adding superoptimizations through integration with Souper. And we now have promising approach for mitigating side channel attacks in Cranelift thanks to researchers at UCSD and the Helmholz Center for Information Security.

Improving testing with fuzzing

If you have lots of people from lots of organizations adding new features, you need guardrails in place to make sure they aren’t breaking each other’s functionality in the process.

One really great way to catch edge case-y bugs is fuzzing. We’ve put substantial effort into building top-notch fuzzing infrastructure. We even became the first project written primarily in Rust to be accepted to Google’s OSS-Fuzz continuous fuzzing service. Since then, OSS-Fuzz has found 80-90 bugs which might not have been found otherwise.

So what kind of fuzzing do we do?

We fuzz WebAssembly execution. As mentioned above, we have the wasm-smith test case generator, which is really good at creating interesting test cases as different inputs for fuzzing. We also do differential fuzzing, comparing results we get with optimizations and those we get without optimizations to make sure that we get the same results. And we do Peepmatic-specific fuzzing, plus various other configurations.

To make sure the calls into the library work, we also fuzz the API. And we fuzz wasm-tools to make sure they can roundtrip everything. If the bytes the fuzzer gives us successfully parse as Wasm with wasmparser, then we will print them with wasmprinter to make sure that they successfully print to the text format, and then we’ll make sure that the text parsers can parse the result.

In Cranelift, we don’t just fuzz at the entry IR level. We also have a second entry point near the end of the pipeline that we can also fuzz at. This makes it a lot easier to hit all of the corner cases of the register allocator algorithm.

And to make sure we continue to have top-notch fuzzing, we’ve instituted a new rule: a feature isn’t considered done until you’ve added fuzzing for it.

Improving documentation

Of course, it’s hard to collaborate on something if you don’t know how it works. To this end, we’ve improved our documentation and examples.

- A tutorial for creating Wasm content and running it in Wasmtime

- Examples for more complex uses of Wasmtime

- Embedding documentation for various languages

We’ll be putting more effort into this over the coming year.

The Lucet and Wasmtime teams join forces

Merging Lucet and Wasmtime has been the plan since we announced the BA. And it’s about to get a lot easier to execute on that plan, since the Wasmtime team is moving to Fastly! 🎉

What does this mean for Bytecode Alliance projects?

Mozilla will continue to have a team working on WebAssembly in Firefox, focused exclusively on the needs of web developers. As part of this, they will continue working on the Cranelift code generator, used by many projects including Firefox, Lucet, and Wasmtime.

Fastly will take on sponsorship for the work on the outside-the-browser projects that were hatched at Mozilla, including Wasmtime and WASI, and we look forward to expanding the scope of that work further.

This is a testament to the collaborative, multi-stakeholder setup of the Bytecode Alliance. It doesn’t matter where we work—we’re still working together.

Bringing all of this to users

This process is all great. But it doesn’t mean anything if we don’t get it into the hands of users.

Here are some projects that are doing just that.

Firefox shipping Cranelift for Arm 64 support

Firefox’s WebAssembly support on x86/x64 has always been best-in-class. However, because of architectural constraints, its performance on Arm wasn’t keeping up. Cranelift was started specifically to get a backend with an architecture that works as well for Arm and other platforms as it does for x86/x64.

This is now bearing fruit. Cranelift is now used by default for WebAssembly content in Firefox Nightly on Arm64 platforms, and work is ongoing to use it on x86/x64, too.

This is another way that the Bytecode Alliance helps accelerate the whole ecosystem. By having our WebAssembly experts team up with the CPU architecture experts at Arm and Intel, we’ve been able to reach better designs that help us move faster and get better results.

Serverless on Fastly’s Edge, powered by Lucet

Fastly’s goal has always been to enable developers to move data and applications to the edge. And recently, they’ve made some huge advances towards that goal using WebAssembly.

They were one of the first companies to see WebAssembly’s potential on the server-side. They’ve since developed that into a serverless compute environment with startup times 100x faster than other alternatives, called Compute@Edge.

Shopify

Shopify powers over one million different merchants globally. And these customers all have different needs.

To keep the codebase and user experience simple, Shopify has a product principle: Build what most merchants need, most of the time. If merchants need features beyond that core set, Shopify provides an App Store with third party apps to solve for that long tail of requirements.

Many of those apps are hosted on their own infrastructure, and during flash sale events are sometimes taken down by the surge in load. To help app developers build more stable apps, Shopify wants to allow app code to run internally right within Shopify.

But how can you run this third-party code in a fast and safe way? By using WebAssembly.

With their new platform, built on top of Lucet, they’ve been able to run a flash sale with 120,000 WebAssembly modules spinning up and executing in a 60 second flash sale window, while maintaining a runtime performance of under 10 ms per module.

Extending Wasmtime for specific use cases

While Wasmtime is a great general purpose WebAssembly runtime, sometimes you want something that is tailored to your use case. A number of developers are building more complex purpose-built runtimes on top of it.

These runtimes will help developers get their products into users’ hands faster.

- Enarx is a Trusted Execution Environment. It keeps your data completely confidential, even from the hardware it’s running on.

- Krustlet is a tool to run WebAssembly workloads natively on Kubernetes.

- WaSCC implements an actor framework for connecting to cloud-native services, such as message brokers and databases.

What’s next?

So what will we be focusing on next?

More members

One big focus is formalizing the governance model so we can bring on new members. There are some fantastic prospective members doing critical work in the ecosystem who we’d love to bring on. To do so, we need to define processes for things like how elections are held and important technical decisions are made. And we need to put all that into bylaws, so our partners know what they’re signing up for.

This year’s crises have distracted from that work, but after adjusting to the new normal, we’ve made good progress. At this point, we’re just working on the finishing touches. Once these are in place, we’ll be able to accept new members and work on scaling the organization.

An MVP of the nanoprocess model

As we mentioned above, both the Module Linking proposal and Interface Types proposals are coming along nicely. We’ll be focused on getting those proposals to an MVP, and implementing support in runtimes and toolchains. We expect to have much of this work done in the first half of 2021.

Better language support

Once the MVP for Interface Types is in place, we’ll be able to start working with language communities to map their language’s types to Interface Types. This way, we’ll be able to have maximum interoperability between modules written in different languages, and easily run these modules in WebAssembly hosts with WASI support.